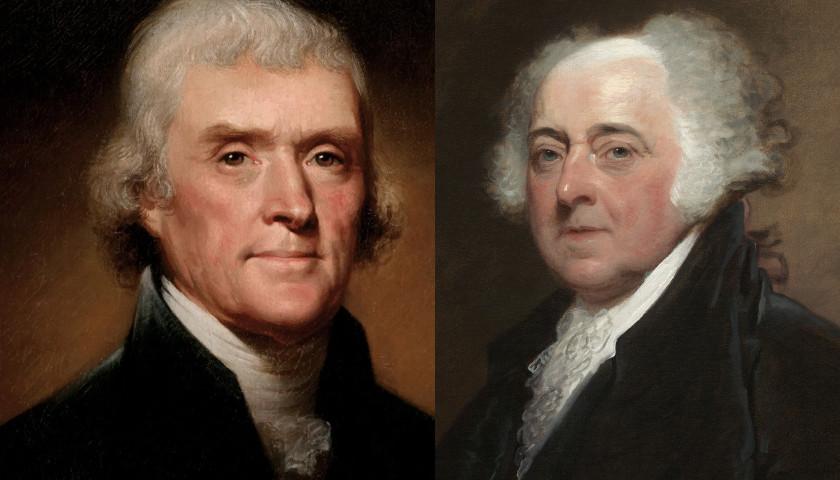

The Library of Congress has some great, but often unused resources. One document I stumbled across mirrors something I had written a few months ago on Thomas Jefferson. The prologue to the article stated: “Thomas Jefferson was an ardent advocate of public education as a cornerstone of a free republican society. Throughout his life Jefferson promoted reform in public education as a prerequisite for an enduring republican nation.” Jefferson understood the value of knowledge for all citizens.

Jefferson is best known for drafting the Declaration of Independence. However, he wrote frequently and passionately about the benefits of a quality education. “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be,” he wrote in a letter to letter to Colonel Charles Yancey. In 1816, Jefferson wrote to P. S. Dupont de Nemours saying: “Enlighten the people generally, and tyranny and oppressions of body and mind will vanish like evil spirits at the dawn of day.”

To secure the widest diffusion of general education, Jefferson, as Governor of Virginia, prepared his “Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge” as part of the change of Virginia’s laws. As chair of the committee, Jefferson proposed a three level system in 1779, (never adopted): three years of primary education for all girls and boys; advanced studies for a select number of boys; a state scholarship to the College of William and Mary for one boy from each district every two years. Although not adopted, Jefferson provided a prototype of the common school movement.

Remarkably, Jefferson did not support compulsory attendance of children. He wrote: “A question of some doubt might be raised…as to the rights and duties of society towards its members, infant and adult. Is it a right or a duty in society to take care of their infant members in opposition to the will of the parent? How far does this right and duty extend? To guard the life of the infant, his property, his instruction, his morals?” Then he added: “It is better to tolerate the rare instance of a parent refusing to let his child be educated than to shock the common feelings and ideas by the forcible asportation and education of the infant against the will of the father.” (Thomas Jefferson, 1817, Bill for Establishing Elementary Schools, in The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. By Albert Ellery Bergh)

As an alternative to compulsory attendance laws, Jefferson recommended another more important inducement: that the “right to vote” would not be granted to citizens that fail to exhibit basic literacy skills. “If we do not force instruction, let us at least strengthen the motives to receive it when offered.” Talk about the carrot and the stick. For added measure, in 1814, Jefferson praised the Spanish constitution because it withheld voting rights from “every citizen who could not read or write.”

Jefferson believed that citizens educated in reading and history could at least follow the news and assess the best way to vote. Of course there wasn’t Internet, 24-hour news channels or fake news during Jefferson’s era. Jefferson had confidence that educated citizens could express themselves adequately to fight, if and when the government infringes upon their liberties.

In writing to Robert Pleasants, Jefferson suggested that the Virginia government even create a public educational system for slaves based on his 1784 plan “for the more general diffusion of Knowledge” as one step in preparing them for freedom. “Ignorance and despotism seem made for each other” wrote Jefferson. Although there is no confirmation that Jefferson taught his slaves to write, he certainly knew and expected that many of them could read his written instructions. The evidence exists of his exchanges between Jefferson and Hannah (b. 1770), a cook and laundress at Poplar Forest, which demonstrates her writing skill and her Christian faith.

On August 19, 1791, Benjamin Banneker, who happened to be born both African-American and free, was also trained as a mathematician, clockmaker, and surveyor, sent Jefferson a copy of his Almanac. In the letter that accompanied the gift, Banneker implored with Jefferson to live up to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson never gave the “aid and assistance” Banneker sought. The letters between Banneker and Jefferson were published regularly by Banneker and his Quaker supporters. Jefferson’s political enemies used this correspondence to allege that Jefferson was a secret abolitionist.

While Jefferson’s place in history is firmly secure, people continue to debate his many ambiguities, trying to line up both his public words and his private actions. It is most certain that Jefferson was not silent on the most effective manner to pass freedom to future generations depended on providing a quality education to our children. An educated citizenry is the roots that our republic is planted on.

##

JC Bowman is the Executive Director of Professional Educators of Tennessee, a non-partisan teacher association headquartered in Nashville, Tennessee. Follow him on Twitter @jcbowman. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided that the author and the association are properly cited.